JAK inhibitors in IBD

A new video, JAK biology, JAKi in UC (tofacitinib, filgotinib and upadacinitinb) and CD (upadacitinib), safety (PRAC 20 and zoster), positioning, future directions

A new generation of medicines for inflammatory bowel disease has entered the clinic.

JAK inhibitors are small molecules that interrupt cytokine signalling. Three molecules have demonstrated effectiveness in UC - tofacitinib (2018), filgotinib (2022) and upadacinitib (2022) - and one in Crohn’s disease (upadacitinib).

Learn all about JAKs in IBD by watching this film and reading on below.

In this edition of Atomic IBD I will cover:

JAK discovery and biology

JAK inhibitors and their selectivity

JAK inhibitors for ulcerative colitis

JAK inhibitors for Crohn’s disease

Safety including ORAL surveillance and the PRAC Article 20

Tofacitinib for acute severe colitis

New molecules

Using JAK inhibitors in my clinic

JAK discovery and biology

JAKs are a family of intracellular tyrosine kinases first discovered by Wilks in 1989.

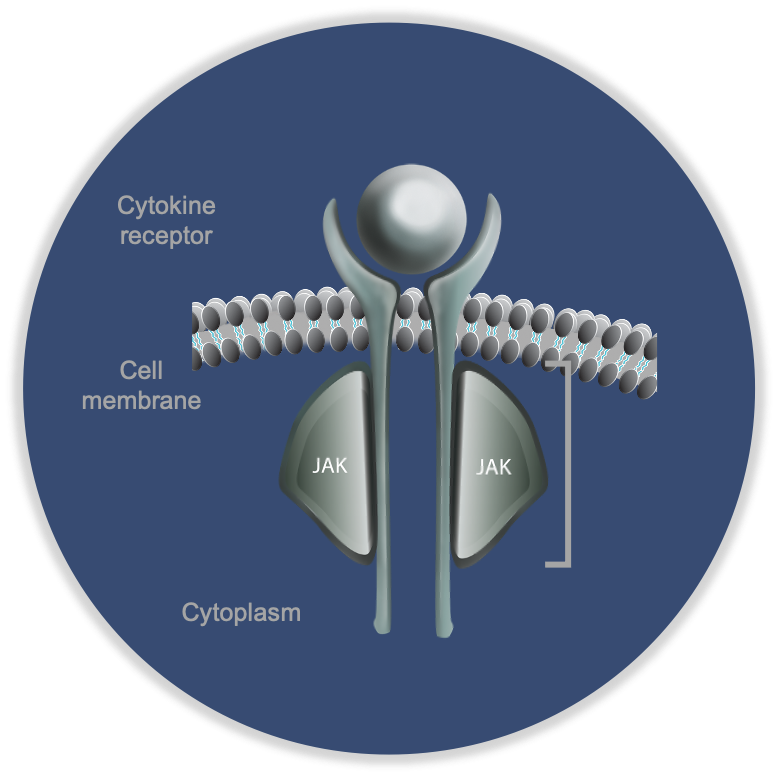

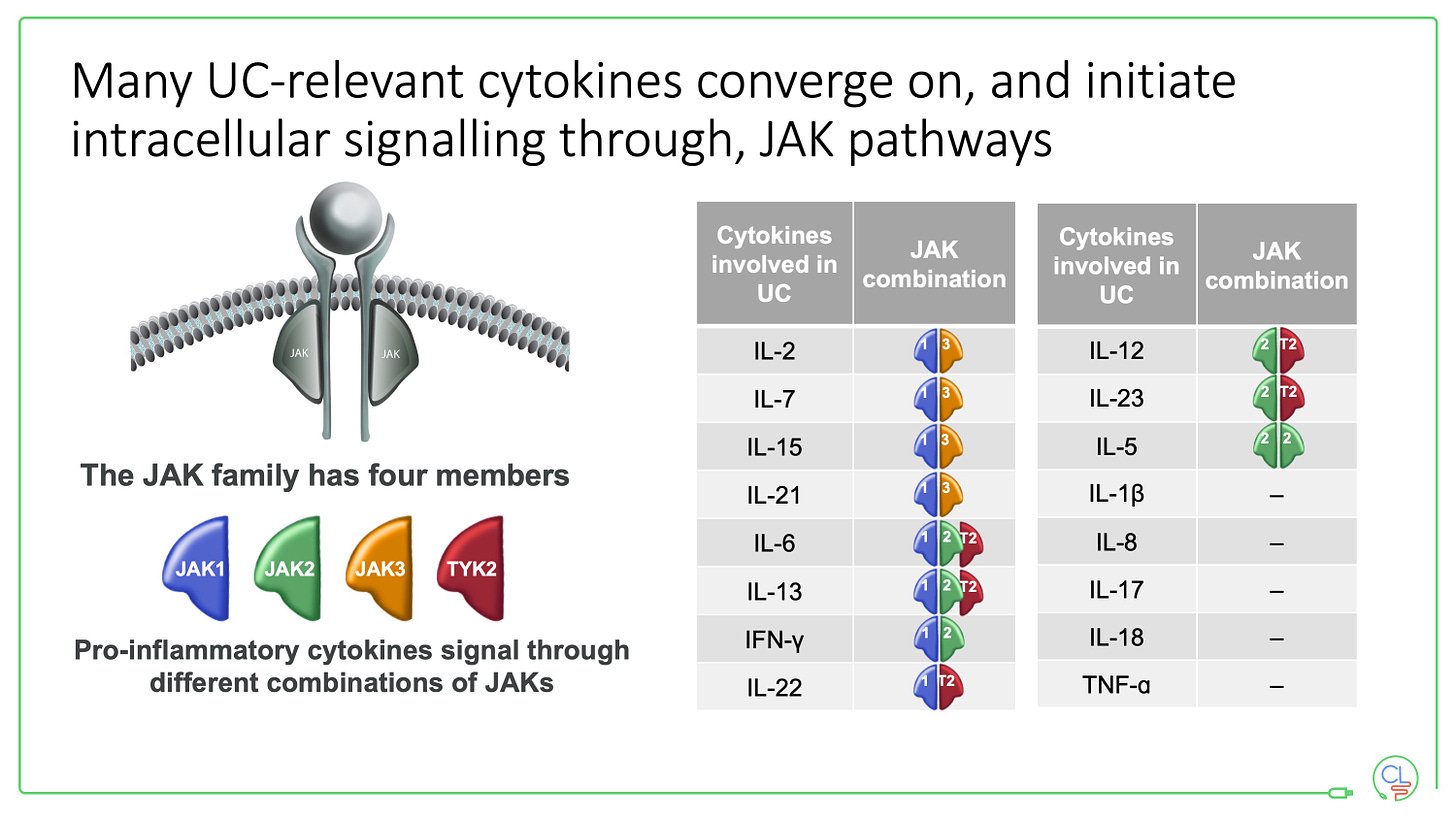

There are four JAKs - JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and TYK2. They function in pairs - as heterodimers - bound to the intracellular portion of cytokine receptors. They are the key molecules that transmit the signal from a cytokine to the nucleus.

When a cytokine (e.g. IL-23) binding to its pair of cytokine receptors (IL-23R), the JAKs spring into action. An ATP molecule binds to a specific groove on the JAK. This ATP binding site is the target for the JAK inhibitors.

After ATP binding, the JAK phosphorylates the intracellular portion of the cytokine receptor. This allows binding of a pair of STATs, which are in turn phosphorylated by the JAK. The phosphorylated STAT complex then leaves the receptor, translocates to the nucleus, binds to DNA motifs and triggers transcription.

This beautiful piece of biology is precisely described. It is the mechanism by which over 60 cytokines signal via homo and heterodimeric interactions of the four JAKs and six STAT proteins.

It is notably that TNF does not signal via JAKs - helping to explain why JAK inhibitors are efficacious when TNF drugs have failed.

There are 11 JAK-STAT signalling genes that are associated with susceptibility to IBD. These include JAK2, TYK2, STAT3, STAT5B, IL2RA, OSMR, SOCS1 and IL23R.

JAK inhibitors and their selectivity

The drugs have pleiotropic effects and should not be considered interchangeable.

The selectivity of the drugs for each JAK protein is determined by in vitro enzymatic assays. Tofacitinib has most of its effect on JAK 1 and JAK3, whereas upadacitinib and filgotinib are more selective for JAK1.

Note that the ATP binding groove, the site of the drugs action, is highly conserved across the four JAKs. No JAK inhibitor is therefore truly selective especially at higher doses.

The impact of selectivity depends on the concentration of JAK inhibitors in the tissues which is influenced by a number of factors including absorption, protein binding, metabolism, excretion, drug-drug interactions, age, sex and genetic polymorphisms.

JAK inhibitors for ulcerative colitis

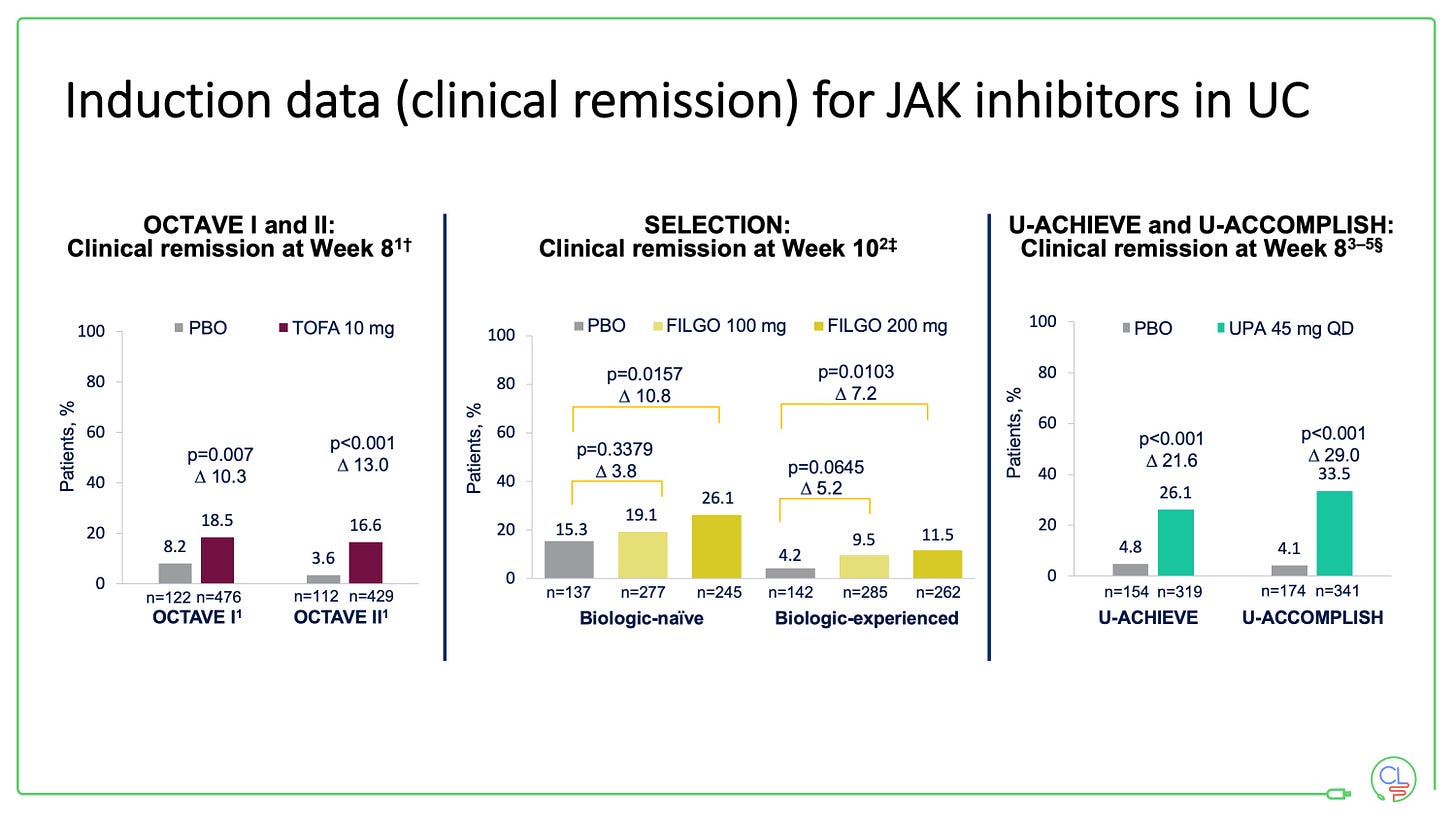

Tofacitinib (OCTAVE), filgotinib (SELECTION) and upadacinitib (U-ACHIEVE and U-ACCOMPLISH) have all been approved for use in UC having met all their key induction and maintenance efficacy endpoints in trials.

All of the drugs work well in patients who are bio-naive and in those who have previously been exposed to TNF drugs. They all work fast, with the trial data demonstrating a significant reduction in stool frequency and rectal bleeding within 1-3 days.

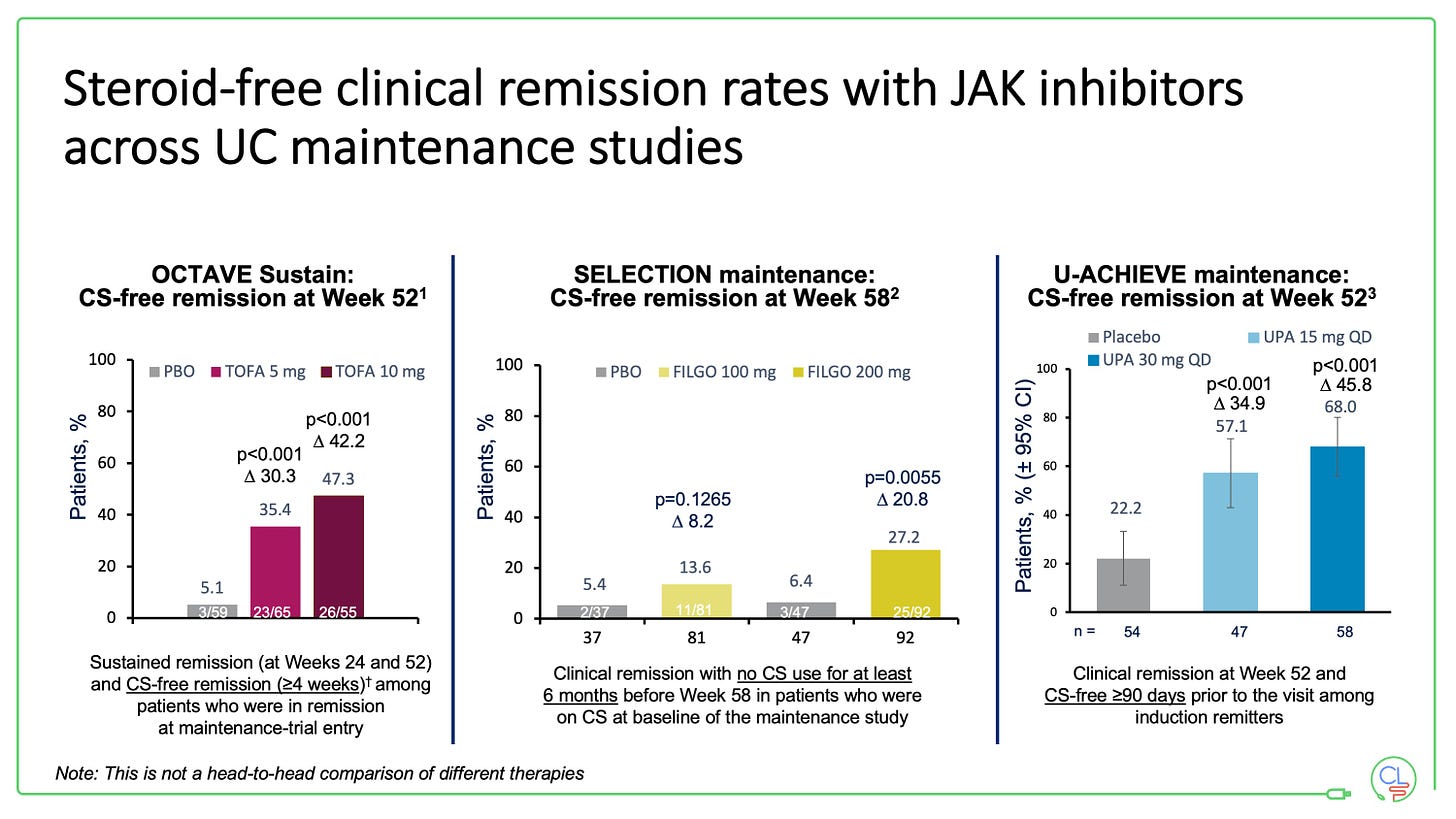

The maintenance studies all re-randomise those patients who respond to induction therapy. All three drugs demonstrated efficacy at a year with respect to steroid-free clinical remission and mucosal healing.

We do not have any direct comparison data between the drugs in UC

Randomised controlled trials of one JAK versus another are unlikely to be performed any time soon - they will need to be large and therefore expensive if done properly.

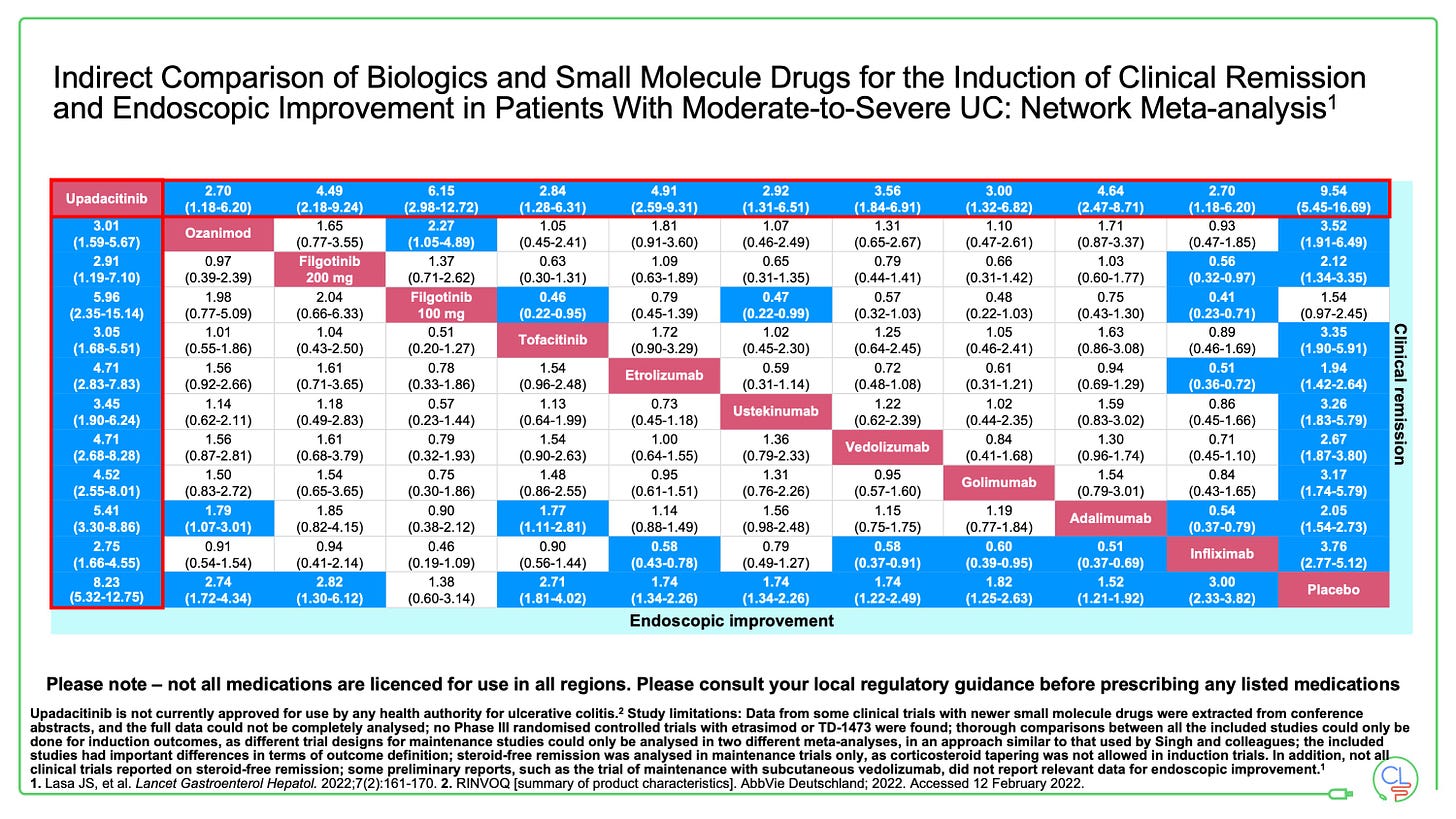

We can make indirect comparisons from network meta-analyses (NMAs).

These show the JAKs work well in UC compared to other therapies. In each of the three NMA’s reported in the 12 months, upadacitinib comes out on top of all advanced therapies for efficacy and endoscopic endpoints in UC.

I expect real-world evidence with propensity score matching to provide some data about relative effectiveness in due course.

These data will be interesting, but will need to be interpreted with some caution.

JAK inhibitors in Crohn’s disease

Tofacitinib did not show benefit in randomised clinical trials for Crohn’s disease.

This may be partly due to trial design and partly limitations of the dose. Our experience in a handful of patients and published data from the TOPIC consortium demonstrate effectiveness in selected patients when used off-label.

Tofacitinib is out for Crohn’s disease then, but upadacitinib is coming.

Upadacitinib has now demonstrated strong efficacy in U-EXCEED and U-EXCEL phase 3 induction studies in a refractory cohort of patients with Crohn’s disease. The 12 week induction period with the 45mg once daily dose met co-primary endpoints of clinical remission and endoscopic response in both induction studies.

Randomised responders were enrolled into the U-ENDURE maintenance study where both 15mg and 30mg once daily doses met the co-primary endpoints of clinical remission and endoscopic response.

There was approximately a 10% delta between 30mg and 15mg doses across all endpoints.

Filgotinib met key endpoints in the phase 2 FITZROY study. The phase 3 DIVERSITY study will read out early 2023.

The PRAC Article 20

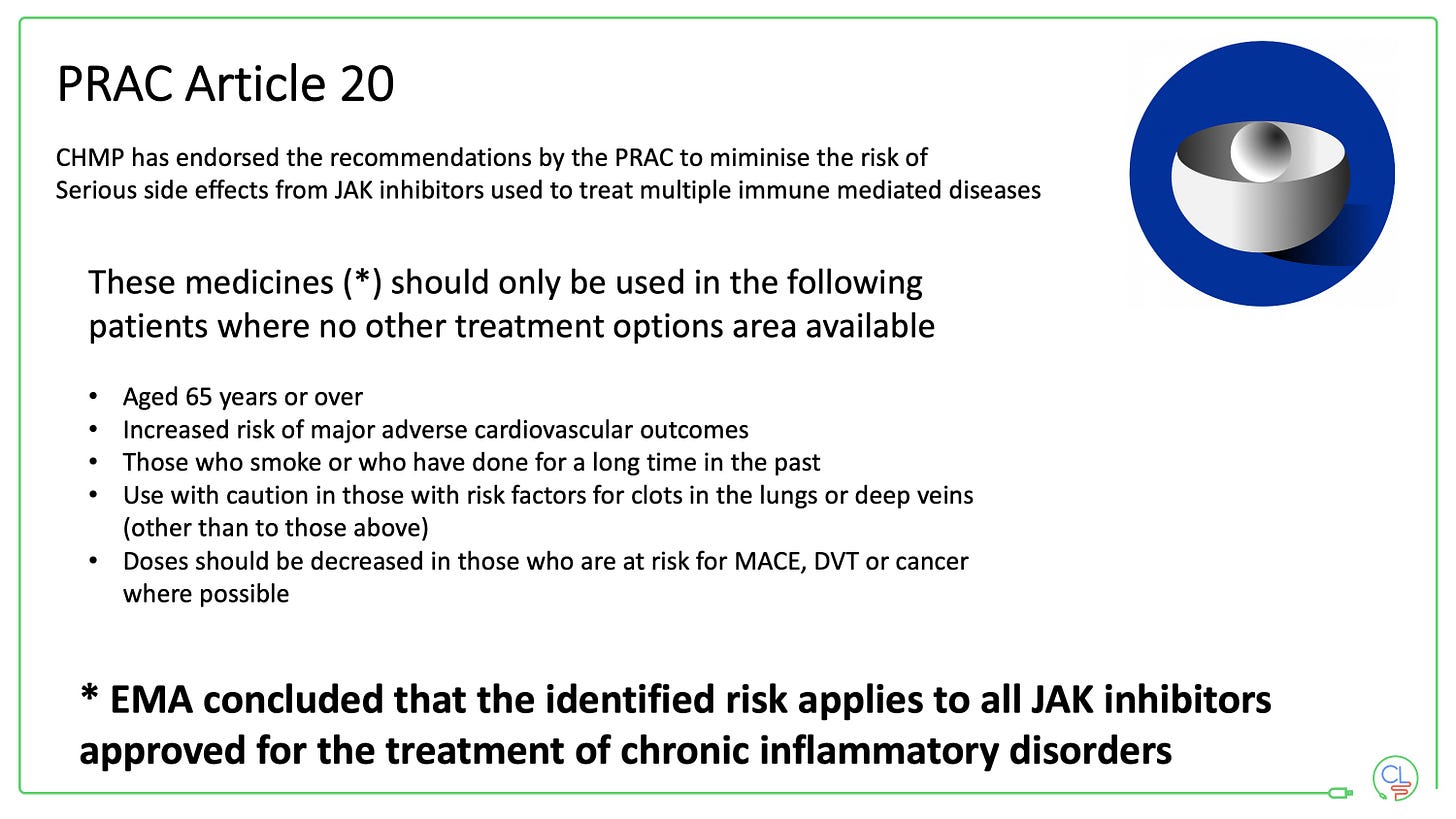

This PRAC Article 20 was triggered by the European Medicines Agency in response to the ORAL surveillance data in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

The ORAL study did not demonstrate non-inferiority between tofacitinib and anti-TNF when both were used in combination with methotrexate for RA in patients who were over 50 years old and had at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The study was endpoint driven and looked at major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and malignancy.

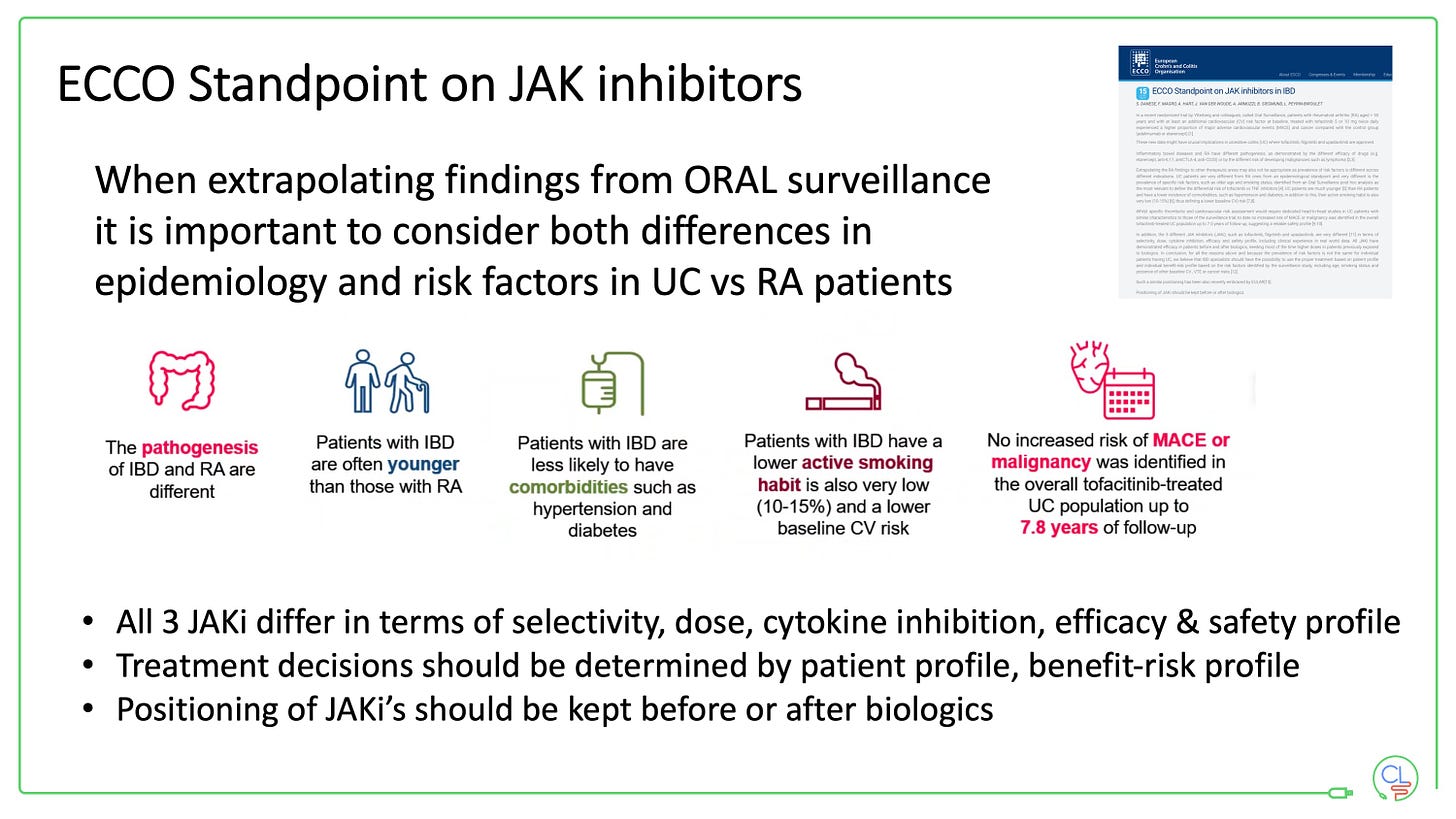

It is important to note that patients with RA are different from those with UC as noted in an ECCO standpoint published this summer.

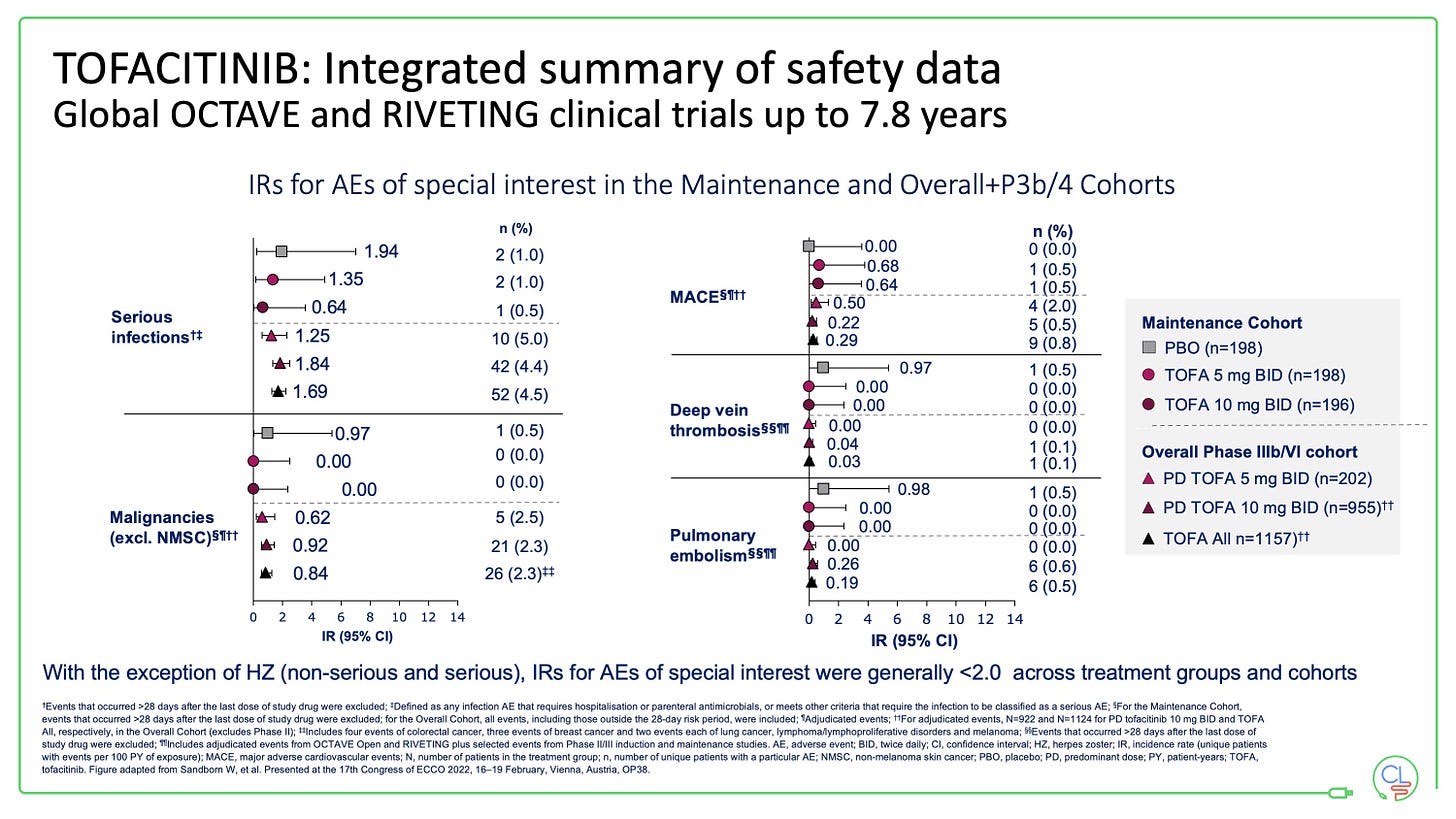

With tofacitinib in UC we now have nearly 8 years of follow-up data from the published controlled studies (OCTAVE and RIVETING).

The only AE of special interest with an incident rate of >2 is herpes zoster. This is rarely dangerous, but can be very unpleasant for patients and will typically interrupt treatment for a period.

However, zoster infection can mostly be prevented by vaccinating against shingles.

This used to require Zostavax - a live vaccine which cannot be used with doses of prednisolone >20mg or within 4 weeks of JAK inhibitor exposure.

Vaccination is now done most effectively with the recombinant GSK vaccine Shingrex. Supply issues limited access to this vaccine outside of the USA until recently. This is largely resolved, however for many the route to vaccination and reimbursement will take some additional work (it has for us locally anyway).

The goal should be to vaccinate all patients with Shingrex prior to / at the point of starting a JAK inhibitor. It may be desirable to vaccinate most patients with IBD at diagnosis, especially those >50 years and those likely to need advanced therapy.

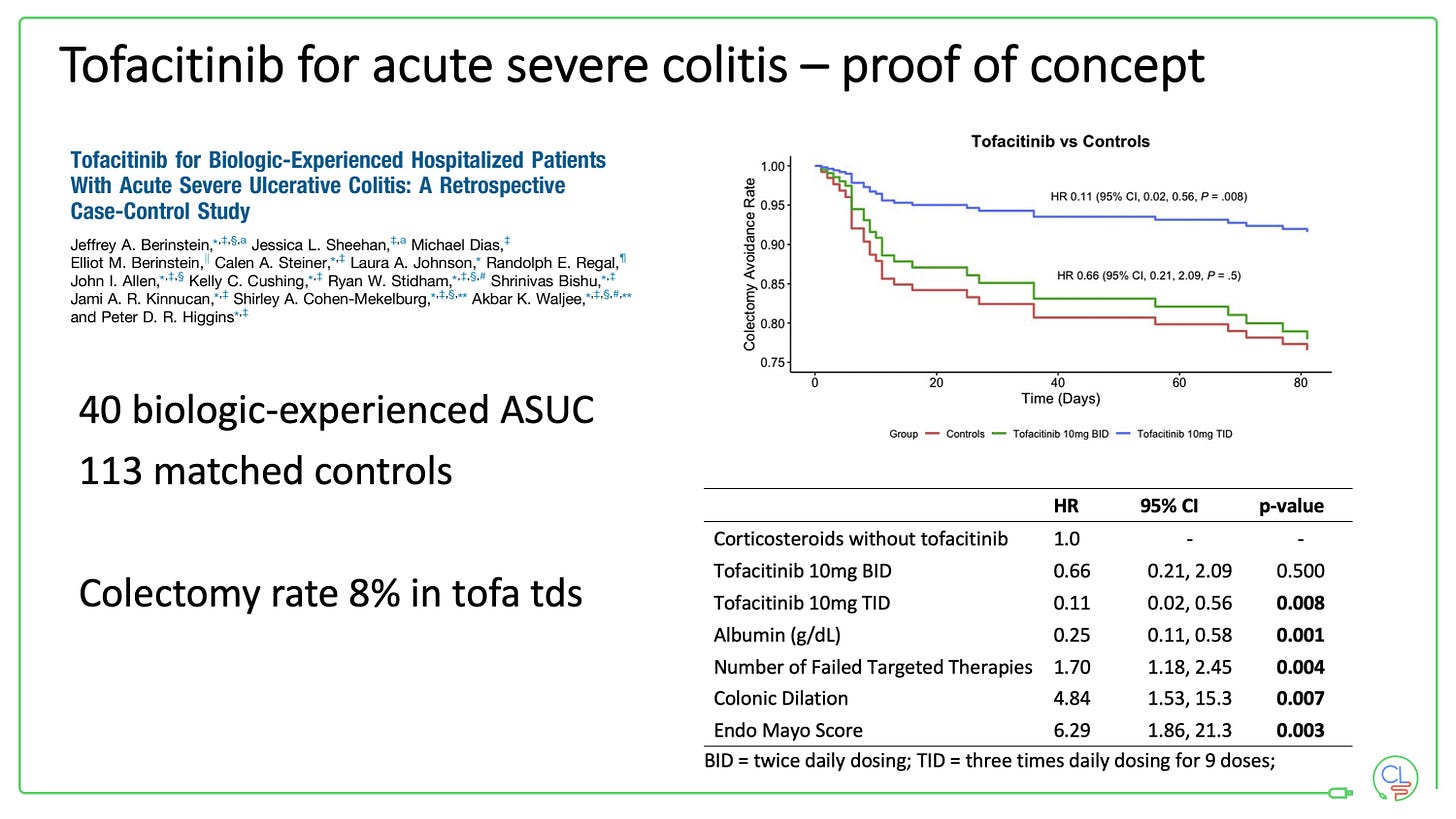

Tofacitinib for acute severe colitis

This is a very exciting potential future avenue for JAK inhibitors.

For now it is off-label and should be restricted to specialised units with very tight monitoring. Don’t forget there is appreciable morbidity with acute severe colitis and colectomy is life-saving for some patients.

The data from North America uses a 10mg tds dosing of tofacitinib for 3 days in patients who have previously failed anti-TNF therapy.

I am very much looking forward to seeing new data emerge here.

New molecules targeting JAKs

Deucravacitinib (BMS) targeting TYK2 did not demonstrate efficacy in the phase 2 LATTICE-UC study. Further testing of this molecule is underway.

VTX958 (Ventyx Biosciences) also targets TYK2 and showed very promising data in extensive phase 1 testing this year.

Ritlecitinib and Brepocitinib (both Pfizer) showed encouraging early phase 2 results this year.

JAK inhibitors are highly effective in the IBD clinic

We have used a lot of tofacitinib for UC in the clinic locally. We have used it first line in younger patients and following TNF failure in many other patients.

It works fast in many patients, slower in some and not at all in others.

The speed of onset with tofacitinib is really very striking. I have many clinical anecdotes of patients who reported feeling considerably better within a matter of days.

The effectiveness in patients who have previously failed other advanced therapies especially anti-TNF is also notable. We had not seen that with vedolizumab or ustekinumab - both of these drugs work much better as first-line biologics in IBD.

The published data and early experience with the newer JAKs is also very encouraging indeed.

How does it work in practice?

Because they are orally active and fast acting, I can see a patient in my Thursday IBD clinic who needs therapy and then:

send labs to confirm flare

send stool culture to exclude infection

send pre-biologic screening tests

issue patient with prescription for JAK inhibitor

patient collects drugs from hospital pharmacy

next morning the specialist nurses phone to counsel the patient

first set of most important screening tests back and clear

start JAK inhibitor within 24 hours of clinic

NO STEROIDS

This is game changing. It allows expedient management of flares without steroids. Hospitalisation decrease. Colectomy rates too.

Very interesting video. What is the projected timeline to approval for upadacinitinb for Crohn's in the UK (England)?

Thanks for sending research information about the role of RAK inhibitors in treating UC and CD. As I looked up all three drugs: tofacitinib, filgotinib and upadacinitinb, none has been approved for CD. Mr. Lees has mentioned that upadacinitinb is still in phase 2 clinical trial for studying its efficacy in Crohn's patients, as I recall. Does that mean it will be several years before it proves effective or not?