When a Billion People Change: IBD and India's Rapid Transformation

Reflections from 72 hours in Hyderabad, my first visit to India.

Hyderabad is some city - 7 million people, crazy traffic, raw energy, huge growth, big tech sector, high-tech hospitals, rapidly shifting environment, but marked inequality. The people are incredibly kind, humble, and hospitable, and they work very hard.

It's hard to imagine how more than a billion people fit in just one country. Somehow it makes more sense in the landmass of China. But in India, it really has to be seen to be believed

The view from Charminar (“four minarets”, 1591) in Hyderabad old city.

It's perhaps even harder to comprehend what happens when a billion people undergo rapid environmental and societal change.

I spoke to clinicians, researchers, coordinators, waiters, drivers, and porters; to people who have lived their whole lives in Hyderabad, to those who have lived and worked abroad for a period and returned, and to those who do outreach work in the villages.

These first-hand accounts tell a remarkable story of transformation.

Everyone now has a smartphone with internet access. This opens vast possibilities, accelerating growth especially with e-commerce and the booming tech sector. But it changes everything, from the philosophies and aspirations of young people to family structure and dietary patterns.

Family structure is changing fast.

Extended families sharing communal home-cooked meals are being replaced by nuclear families where both parents work and food is delivered via an app. Young people are marrying much later or not at all, and the birth rate is declining.

Hyderabad is now the IT capital of India, eclipsing Bangalore where the city's infrastructure is struggling to catch up to the past decades' growth. It's an attractive destination for many who have migrated here from nearby villages and further afield, drawn to the job market and an increasingly westernised lifestyle.

This is really the epitome of urbanisation, the key epidemiological signal when one looks at the shifts in IBD incidence in newly industrialised countries.

Rates of infectious illness are declining, while non-communicable chronic illnesses – obesity and associated cardio-metabolic diseases and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases – are rising.

There is undoubtedly a seismic shift in habitual diet underlying at least some of these changes. Meat consumption has soared; this is reflected in data showing an association with ulcerative colitis susceptibility.

But recent focus has been on ultra-processed foods (UPFs), now ubiquitous across the world, driving not just increased calorie consumption, but also changes in our gut microbiota and inflammation. UPF consumption has been associated with Crohn's disease risk in several North American and European cohorts.

In rural settings, there are changes too.

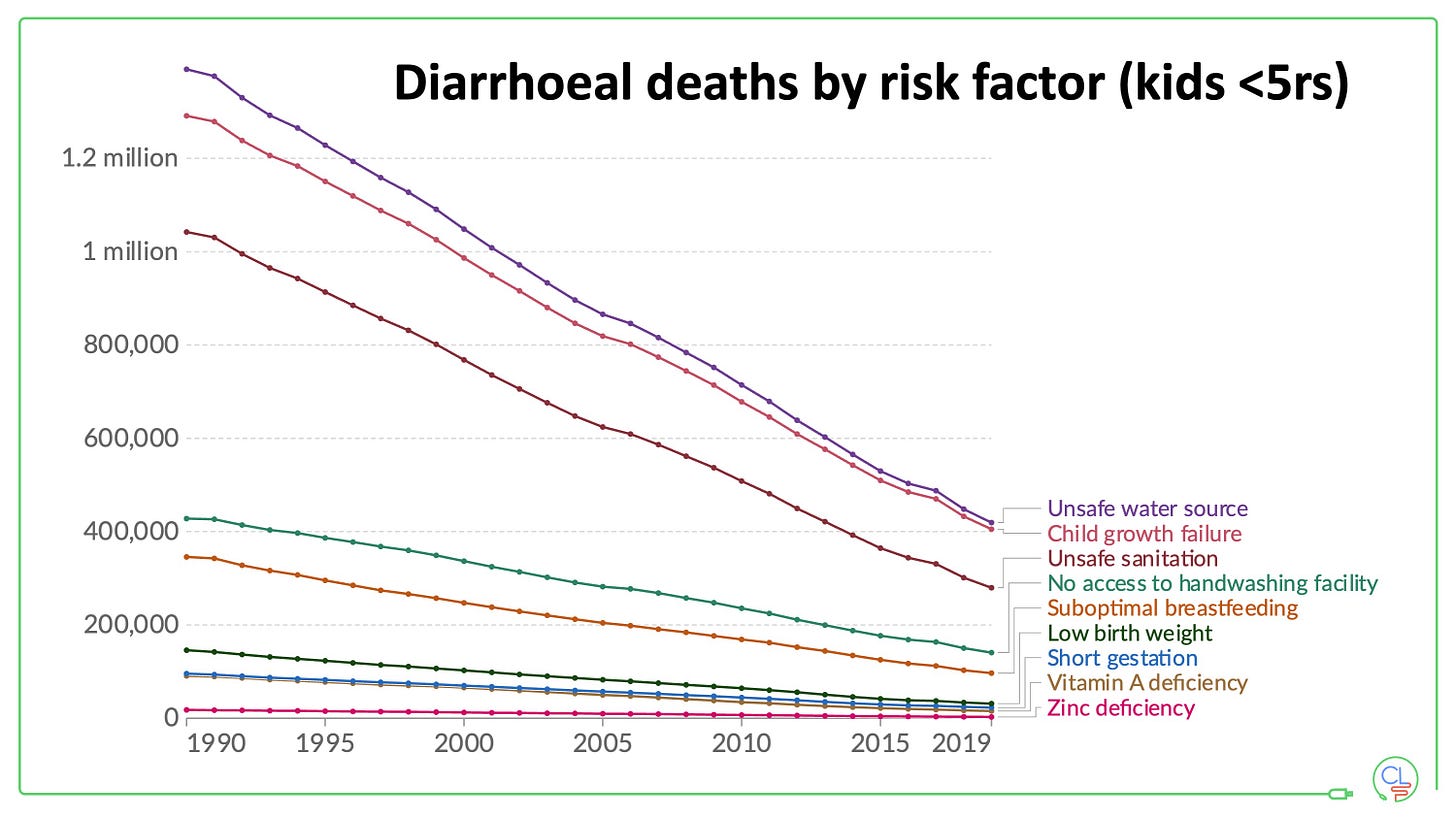

Sanitation is vastly improved, and antibiotics are widely available. This is largely a success story – diarrhoeal deaths in young children across the world have fallen substantially in the past 3 decades.

That may be where the good news stops. Village shops now sell more UPFs than traditional foods. Increasing numbers of people live with overweight and obesity. And the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease is, by some estimates, already similar to that in comparable urban settings.

So what does the future hold?

There will be major infrastructure, economic, and healthcare challenges to satisfy the demands of a people hungry for change. How do you feed a billion people without UPFs? How do you ensure that the very poorest aren't left behind, even once you have lifted them from extreme poverty?

But there are enormous possibilities too.

India is well-poised to reap the harvest from the technological revolution, with a motivated workforce adopting mobile technology, universal internet connectivity via low-earth orbit satellite constellations, and artificial intelligence.

Demographic and environmental change, climate, and geopolitics can all be observed through the lens of inflammatory bowel disease.

IBD does not respect age, gender, ethnicity, or social status, and increasingly the same can be said for geography. At the end of the day, there is a human being living with an intrusive and debilitating chronic illness and clinicians doing their best to care for them. It matters not what your political or cultural beliefs are.

Everyone deserves the same high-quality, compassionate care.

And so we should raise awareness, improve standards, and double down on our efforts to understand the true nature of these illnesses, so we can start the hard work towards prevention and cure.

Lighting the lamp to open the first IBD Conclave at Yashoda Hospitals, Hyderabad organised by Dr Kiran Peddi, Gastroenterologist.

As a Crohn's patient of 19 years, you give me so much hope <3 Thank you.