The PREdiCCt Study: Can we predict IBD flares?

PREdiCCt is out today in Gut

This is the first major paper from a large UK prospective cohort designed to answer a deceptively simple question: when people with IBD feel they are in remission, what actually predicts who will flare next?

The Journey

We started PREdiCCt in 2016 with a deliberately ambitious aim: build a deeply phenotyped cohort in routine clinical care, capture diet and lifestyle data prospectively, and link this to clinically meaningful outcomes over years, not months.

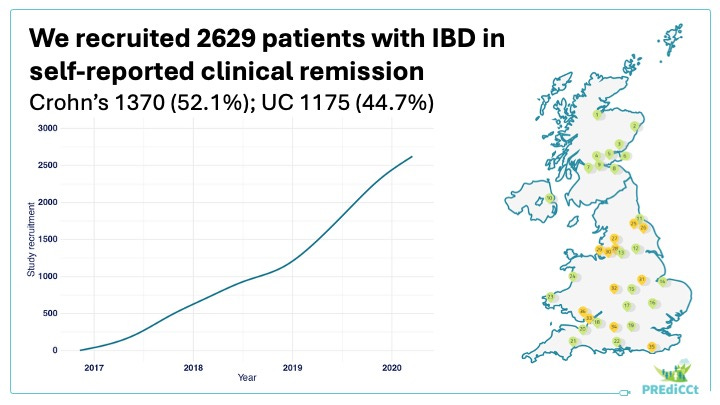

We recruited 2,629 people in self-reported remission across 47 NHS centres, collected detailed baseline data including faecal calprotectin and validated dietary questionnaires, and followed them for a median of just over four years.

Two flare definitions, on purpose

IBD flare is not a single concept, and treating it as one is a major source of confusion in both clinical practice and research.

In PREdiCCt, we separated them deliberately:

Patient-reported flare

Defined via monthly questionnaires, using the question: “Do you think your disease has been well controlled in the past 1 month?”Objective flare

Required symptoms plus treatment escalation and biochemical evidence of inflammation, defined as CRP at least 5 mg/L and/or faecal calprotectin at least 250 µg/g.

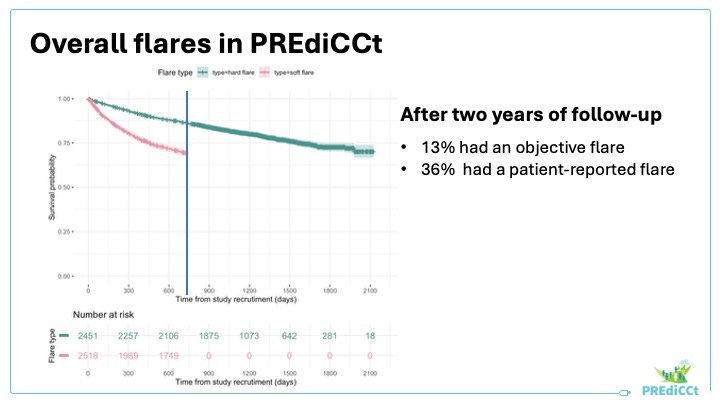

Over 24 months, patient-reported flares were common (31%). Objective flares were less frequent (14%). That disconnect is not a footnote. It is one of the central messages of the study, and it sets up what is coming next.

The symptom-inflammation disconnect is not a footnote here. It is one of the central messages.

The early warning signal

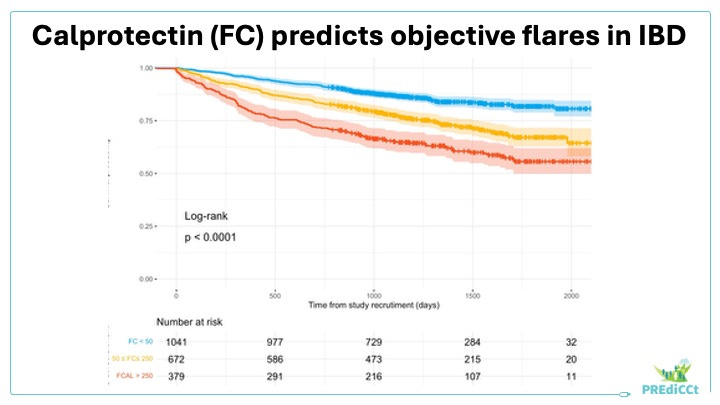

Baseline faecal calprotectin was the strongest predictor of future flare across both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Two things matter clinically. First, the signal was dose-responsive: even in people who felt perfectly well at enrolment, higher calprotectin translated into higher subsequent risk. Second, the “grey zone” mattered. Risk was meaningfully increased even in the 50–250 µg/g range, compared with levels below 50.

To make that tangible: in ulcerative colitis, the probability of an objective flare within two years rose from 11% in those with baseline calprotectin below 50 µg/g to 34% in those above 250. Subclinical inflammation carries a real cost, even when symptoms are quiet.

This reinforces a simple point: subclinical inflammation carries a real cost, even when symptoms are quiet. It also raises an important question for treat-to-target practice, where FC thresholds of 250 µg/g are often used pragmatically.

PREdiCCt suggests that more stringent targets may be required for truly low relapse risk.

The diet signal in ulcerative colitis

Diet is where the evidence has often been loud and thin. PREdiCCt brings more signal and less speculation.

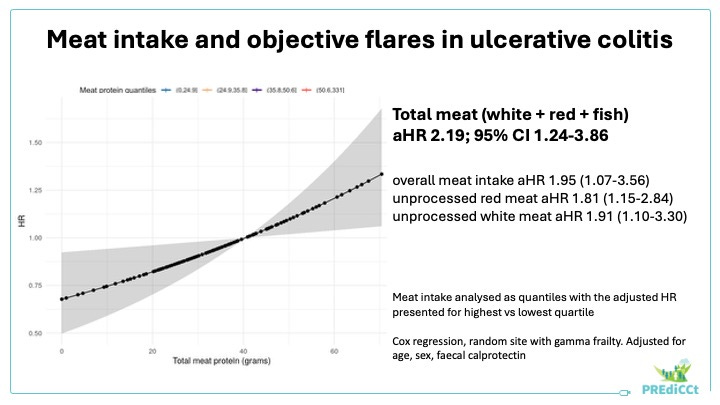

In ulcerative colitis, higher habitual total meat intake was associated with roughly double the risk of an objective flare. The absolute two-year risk rose from 12% in the lowest quartile of meat intake to 26% in the highest. When we looked at granular categories, the strongest signals were for unprocessed red and white meat. Fish was not associated with flare risk.

Just as importantly, we need to be explicit about what we did not show. We found no consistent associations between objective flares and ultra-processed foods, dietary fibre, polyunsaturated fatty acids, or alcohol. And we did not see these dietary associations in Crohn’s disease.

What this means

This paper is the opening chapter, not the full story, but it gives us a practical foundation for preventive care.

If we want to prevent inflammatory flares, we need to use biomarkers like calprotectin proactively rather than reactively. The ulcerative colitis meat signal is credible and actionable, and it should now motivate targeted intervention trials rather than sweeping dietary claims. And recognising the difference between symptom flares and inflammatory flares helps patients, clinicians, and researchers interpret signals correctly.

The team and what comes next

This study was a decade in the making and represents a huge collective effort across data scientists, research nurses, and investigators from the UK.

Most importantly, it was made possible by 2,629 people living with IBD who gave their time and trust. This work exists because of you.

PREdiCCt has much more to say. Next come the psychosocial analyses, which sit naturally alongside the symptom-inflammation disconnect highlighted here, and the deep metagenomic analysis of the gut microbiome.

The short version: feeling well is not the same as being at low inflammatory risk. PREdiCCt shows us how to tell the difference

Key points

We recruited 2,629 people with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or IBD-unclassified in self-reported remission from 47 UK centres, and followed them for a median of just over 4 years.

We deliberately separated symptom flares from inflammatory, treatment-escalating flares by using two endpoints: patient-reported flare and objective flare.

Over 24 months, patient-reported flares were common (31%), while objective flares were less frequent (14%).

Baseline faecal calprotectin (FC) was the strongest predictor of both patient-reported and objective flares, including within the 50-250 µg/g range.

In ulcerative colitis, higher habitual total meat intake was associated with higher risk of objective flare (around doubled risk comparing highest vs lowest quartile).

We found no consistent associations between objective flare risk and ultra-processed foods, dietary fibre, polyunsaturated fatty acids, or alcohol intake.

The symptom-inflammation disconnect is not a footnote in PREdiCCt. It is one of the central messages, and it sets up what is coming next, especially the psychosocial work.

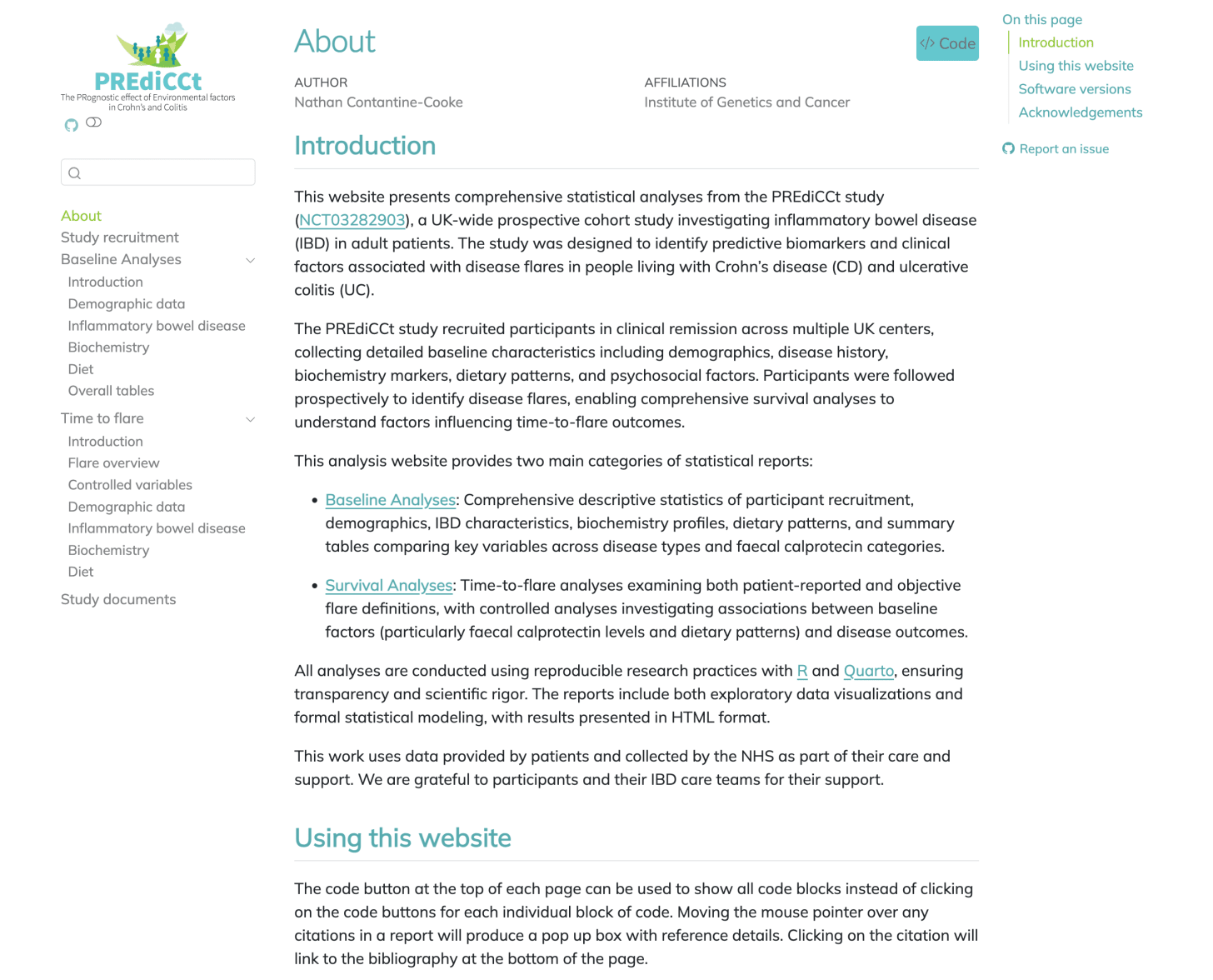

Browse the data online

You can browse the full PREdiCCt dataset here thanks to the brilliant Nathan: https://www.constantine-cooke.com/predicct-analysis/

Thanks for sharing a summary of the research, this is really interesting! I had some quick questions on the predictiveness of faecal calprotectin. Does that imply that it would make sense to take samples a lot more regularly and then proactively adjust medication? Or what other things could be done proactively if we know in advance that there is this elevated risk?

Thank you very much for this fascinating work in such an important field.

As a patient advocate, I find the discrepancy between subjective experience and objective evidence of a flare particularly interesting.

While this is not fundamentally new, seeing it laid out so clearly is truly striking.

It would certainly also be interesting to understand how these differences arise.

Do subjective flares perhaps progress into objective flares at a later point in time?

Could subjective flares be driven by subclinical inflammation?

And where do these functional symptoms originate from?

Of course, none of us are interested in dismissing or invalidating patients’ lived experiences, so i am interestet in your perspective on this :)