I don't believe diet is the primary cause of IBD.

There's no doubt that the incidence of IBD has increased worldwide in parallel with the adoption of a Western diet. This trend can be traced back to the post-war period across North America and Europe, and much later in newly industrialised countries. But many other aspects of our environment have changed too – urban living, smoking, antibiotics, hygiene, stress, exercise, air pollution - to give just a few examples.

But diet is under the spotlight, not least because, along with smoking, it is the ultimate modifiable environmental factor.

I visited China in 2013 (Guangzhou) to provide the first ECCO-supported summer school in IBD. Gastroenterologists from across the country came to learn how to manage Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Until recently, they had never encountered a case, but now their clinics and wards were full.

That trip opened my eyes to the accelerating incidence of IBD in the far East.

It also highlighted the rapidly shifting environment across the region. The juxtaposition between old and new was everywhere and jarring. The hotel's morning buffet offered traditional delights (congee and noodle soup) alongside processed bread and breakfast cereals. In the city centre, old market stalls desperately vied for customers, bathed in the glow of dominating fast-food outlets.

Each time I visit a newly industrialised country a similar story emerges.

This presents a compelling narrative: IBD is an illness of modern living. Its incidence has increased rapidly worldwide as countries have adopted a Western diet. The epidemiological trends strikingly align with obesity and type 2 diabetes.

However, they also align with multiple other indices of industrialisation. In fact, urbanisation is the primary epidemiological signal.

So what direct evidence do we have for the role of diet in IBD aetiology?

Several large cohort studies have provided key insights, mostly painting a consistent picture:

· Diets high in red meat and sugar are associated with an increased risk of ulcerative colitis.

· Diets high in ultra-processed food but low in fibre are associated with an increased risk of Crohn's disease.

These data come from the Nurses' Health Study (I and II), the EPIC Cohort, the PURE study, NutriNet-Santé, and UK Biobank. All these studies have remarkably similar strengths and weaknesses.

They are large and prospective, with dietary data collected at baseline using food frequency questionnaires. With long follow-up times, most have accrued large numbers (in the several thousands) of incident IBD cases. Additional baseline data allows for at least some control of multiple confounding factors.

However, they were all set up to examine lifestyle and environmental factors associated with diseases of ageing – cancer, cardiometabolic disease, neurodegenerative disease, and death. As such, most have a median age at recruitment of about 50 years.

Exploration of these cohorts to study IBD needs to be interpreted considering:

1. These studies were not set up to look at causes of IBD.

2. The incident cases are much older than in the general population.

3. Incident cases are identified by linkage and only have partial data available.

4. Not all confounding factors can be addressed.

They also look at diet measured at a single time point during adult life, so they don't factor in childhood diet – we know that early life environment is very important in the development of IBD.

A couple of other key points:

FFQs are not designed to look at ultra-processed foods (UPFs), and the NOVA classification is retrofitted based on certain assumptions; indeed, most of these cohort studies were initiated long before the term UPF was even coined.

Many publications looking at dietary and environmental factors and IBD incidence in these cohorts are reported in isolation from each other.

There is a significant risk of residual confounding.

This makes sense if you consider the broad environmental changes and the correlation between multiple lifestyle factors. "Healthier" people tend to have a "better" diet, be more affluent, smoke less, exercise more, and have better access to healthcare – to name just a few examples.

Modifying our diet means a radical rethink of the entire food supply chain.

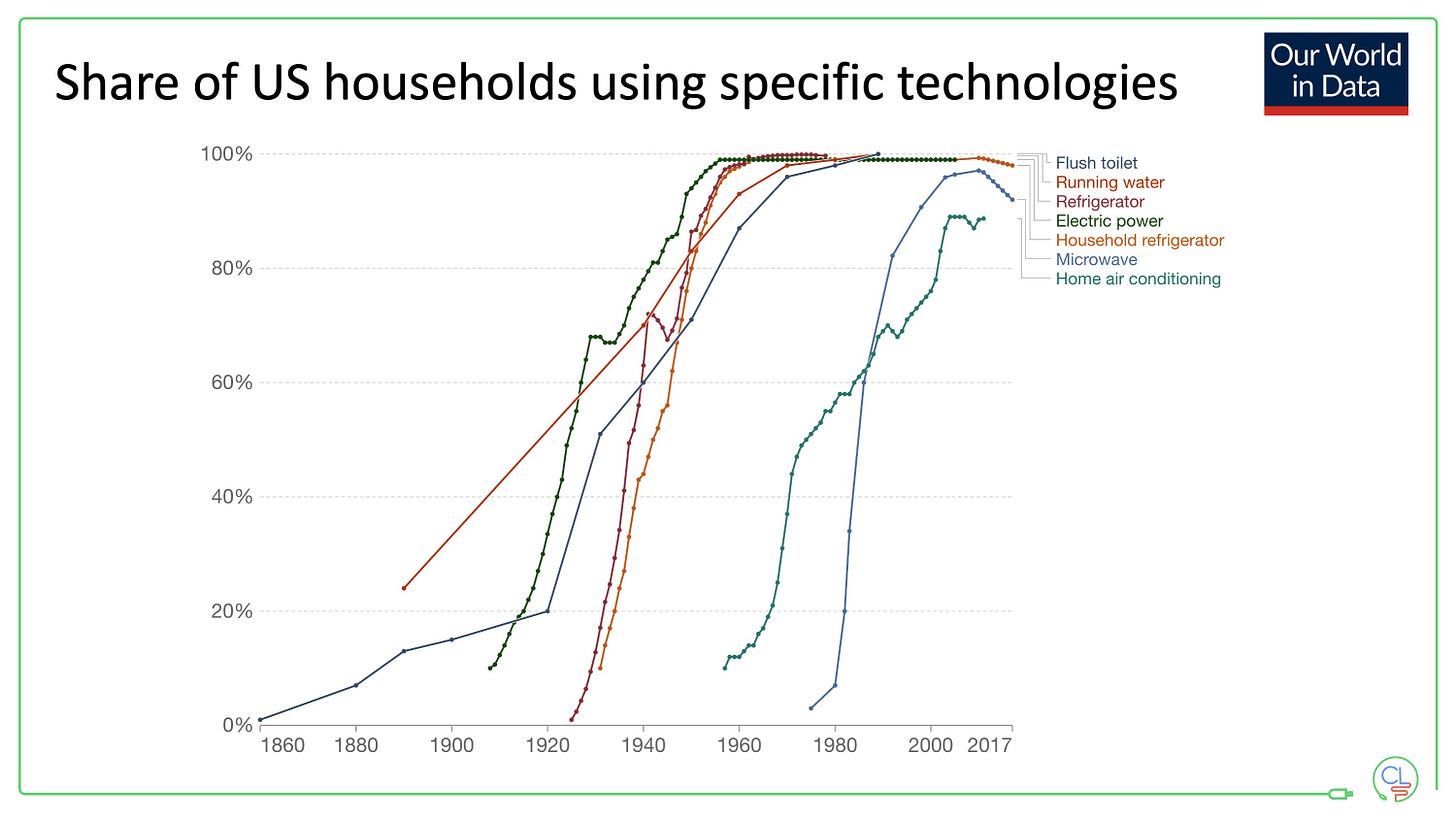

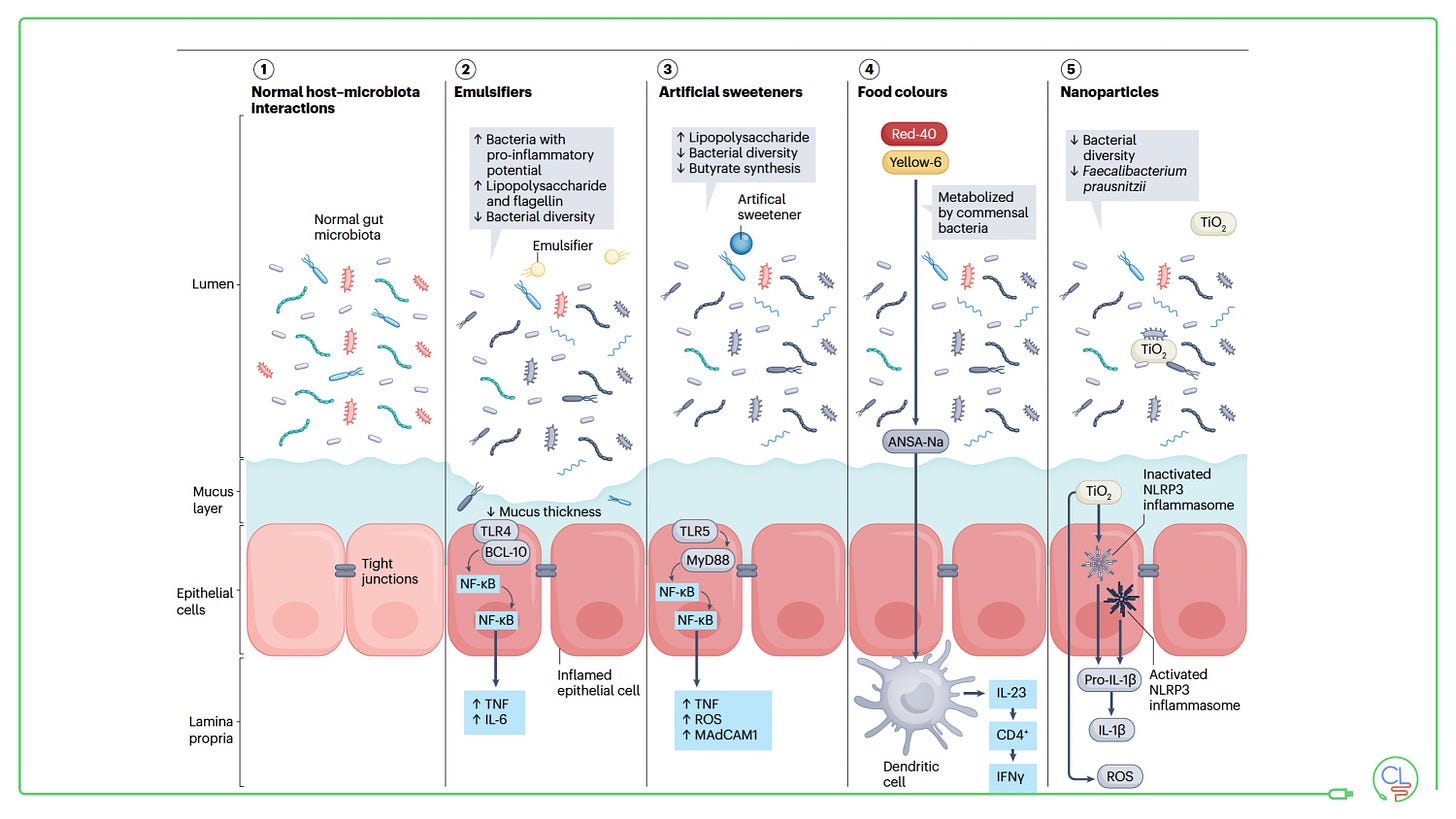

Every aspect of food production, harvesting, storage and preparation has changed beyond recognition in the past decades. Domestic refrigeration did not exist anywhere before the Second World War! Our food is mass produced in factories using industrial machinery and high-tech chemistry. Much of this makes its way directly into the food we consume everyday – including food colourings, emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, nanoparticles and microplastics.

There is undoubtedly a compelling picture here, one that is now supported by multiple lines of evidence from elegant mouse studies and interventional human studies.

The modern Western diet is not just responsible for rampant obesity, diabetes and heart disease, but is at least in part responsible for the massive global increase in IBD.

Tackling that is a major issue which we will come to later.

Why don’t GI doctors refer patients with IBD to dietitians? There are so many nutrition issues.

I am SO glad that I am a dietitian. It has saved me a lot of suffering with ileal Crohn’s disease.

Refer, refer, refer!!!!!

Food and diet could be the cause but only part of it at most.

I’d say the aetiology proposed by Anthony Segal makes the most sense to me:

- putting CD and UC under the umbrella term IBD doesn’t help much

- CD is caused by a defective innate immune system, hence call of duty of our adaptive immune causing hallmark granulomatus inflammation

- genetic predisposition but there must be a trigger e.g. an acute GI infection